Wyndham Lewis and Francis Bacon

By Jan Cox

Wyndham Lewis became an art critic for The Listener soon after the Second World War and was an early and impassioned voice in support of the artist Francis Bacon. Lewis wrote about Bacon from 1946 until near the end of his writing career in 1954; his positive criticism of Bacon’s Hanover Gallery exhibitions of 1949 and 1950 are of particular significance. Bacon expert Michael Peppiatt explains how Lewis ‘led the way with a review of the artist’s first show [...] that was so far-seeing it can still be read with benefit today’ (Peppiatt 2006, 34). Lewis’s writing was both fervently descriptive and critically incisive and in November 1949 he declared that ‘Bacon is one of the most powerful artists in Europe today and he is perfectly in tune with his time’ (Lewis 1949c, 860). Lewis’s enthusiasm is demonstrated by visits to the Hanover in advance of the 1949 and 1950 exhibitions; in The Listener he discussed Head III in May 1949 and, briefly, three of the Study after Velázquez series in September 1950. His enthusiastic commentary on the latter proved premature, in that the pictures were withdrawn before the exhibition even began. However, as is discussed in detail later, Lewis’s observation of these three canvases crucially disproves Robert Melville’s assertion, subsequently repeated by Ronald Alley (1964, appendix B: D6) and David Sylvester (2000, 44), that ‘the third version never saw the light’ (Melville 1951, 63).

Francis Bacon believed that his artistic career began with Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (Tate Britain; 1944), a work that was exhibited at the Lefevre Gallery in London in the spring of 1945. Interestingly, the two critics who reviewed this early display of Bacon’s talents were both known to Wyndham Lewis. In 1948 Lewis described Raymond Mortimer, who had attacked his America and Cosmic Man, as ‘an old Bloomsbury [whose] acquaintance with American history is probably no more than you could put in a thimble’ (Rose 460-1). The other — and very different — reviewer was Michael Ayrton, who was to become a good friend to Lewis, and often acted as his ‘eyes’ after Lewis went blind.

Mortimer was the first of several critics to contend that Bacon’s abilities were compromised by his choice of ‘shocking’ subject matter. In April 1945, Mortimer described the ‘ostrich necks and button heads’ of Three Studies as ‘gloomily phallic (Bosch without the humour)’, and then continued:

I have no doubt of Mr. Bacon’s uncommon gifts, but these pictures expressing his sense of the atrocious world into which we have survived seem to me symbols of outrage rather than works of art. If Peace redresses him, he may delight as he now dismays. (Raymond Mortimer New Statesman and Nation, 14 April 1945, 239.)

|

© Tate London 2009 |

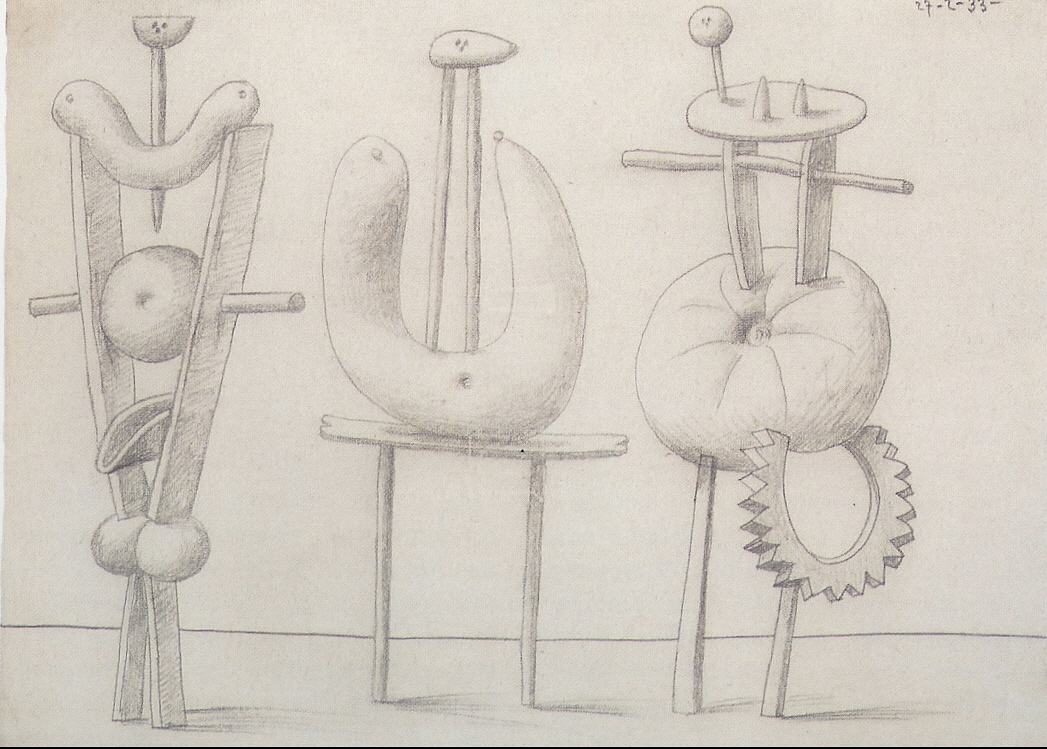

Michael Ayrton also believed that Bacon possessed power, but saw Three Studies as ‘completely under the influence’ of Picasso’s “bone” period (1932-33), in which, said Ayrton, ‘Picasso reduced the gigantic achievement of Grünewald’s Isenheim Crucifixion to a series of French loaves, putty and damp cloth’ (Ayrton 335). Indeed, Bacon had produced three known works on the subject of the Crucifixion itself in 1933, the same year that some of Picasso’s Crucifixion and Une Anatomie drawings appeared in the French magazine Minotaure.

|

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2008 |

Ayrton’s antipathy towards Picasso — he had described him as a ‘master of pastiche’ in 1944 — accounts for his muted praise of Bacon’s work. However, as Picasso’s reputation revived in the years following the Second World War, Ayrton found himself increasingly isolated in the British art world.

No such reservations assailed film critic and author Roger Manvell (writing as Roger Marvell), who observed Bacon’s Figure Study I and Figure Study II at the Lefevre Gallery in February 1946. In a show in which Ben Nicholson and Graham Sutherland were officially headlining (Bacon shared second billing with Colquhoun, Craxton, Freud, MacBryde and Trevelyan), Manvell wrote in the New Statesman:

There is nobody in England who can paint better, and only two or three who can paint anything like as well [...] the handling is consummate. I should suggest an affinity with Velázquez ’s, if I did not know that somebody would at once attribute to me the view that Mr. Bacon is as great a painter as the Spaniard. [...]I find his compositions hard to grasp. But what excitement to find in a young English painter such staggering virtuosity (Roger Manvell New Statesman and Nation, 16 February 1946, 19.)

It is interesting to observe Manvell’s reference to Velázquez three years before Bacon’s Head VI refers made the first compositional reference to the Spanish painter’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650: Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj). Additionally, Manvell’s cinematic books such as Film (1944) and The History of the British Film 1896-1906 (1948, co-authored with Rachael Low) provided Bacon with a rich source of images (Harrison 2005, 95-96), exemplified by the much-discussed Odessa steps sequence from Eisenstein’s film The Battleship Potemkin. Bacon would have read Manvell’s description of this scene as ‘possibly the most influential six minutes in cinema history’ (Manvell 1944, 47-48).

Wyndham Lewis on Bacon

Wyndham Lewis first indicated the esteem in which he held Francis Bacon in an article published in December 1946:

A visitor to London galleries, seeing the Picassos brought here by the British Council, seeing Jack Yates vying with Matthew Smith in dashing density of pigment, with cliffs of paint making all contour superfluous; seeing Graham Sutherland or Mr Bacon cheek by jowl with the late Mr Wilson Steer [...] would undoubtedly receive an impression of inconsequence and chaos [...] But what of it! This confusion is a healthy sign [...] It shows that the national barriers have been broken down [...] we are beginning to have a genuine international, or cosmic, culture. (Wyndham Lewis ‘Towards an Earth Culture or the Eclectic Culture of the Transition’ The Pavilion, A Contemporary Collection of British Art and Architecture, December 1946, Myfanwy Evans (ed.) (Michel 381-382).)

(Lewis’s last sentence is a precursor to Marshall McLuhan’s assertion of a ‘global village’ — Lewis discussed the general concept with McLuhan in North America from 1943 onwards).

Lewis includes Bacon with much better-known artists here, awarding him a pre-eminence that he had not then achieved in British art. However, Lewis’s initial praise of Bacon’s work was followed by a period (until November 1949) during which Bacon failed to exhibit — the artist destroyed all the work he created between Painting (1946) and Head I (1948).

During the hiatus in the exhibition of new Bacon pictures, David Sylvester, then signing himself as A. D. B. Sylvester, addressed the ‘problems of the painter’ in an article published in the French journal L’Age Nouveau in 1948. Sylvester placed Graham Sutherland, Jankel Adler, Robert Colquhoun, Robert MacBryde, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth at the forefront of artistic creativity in Britain and had this to say of Bacon:

Francis Bacon, who is around 40 years old, is the heir to some aspects of expressionism — such as features of Soutine — and Picasso’s surrealist period. His works are never free of brutal horror [...] he borrows the forms of the Crucifixion which evoke that of Grünewald, the Germanic manner that the delirious epileptic seems to possess. It is his weakness — the vision it possesses, he does not possess — but he is one of the most dramatic and most powerful of current painters. (David Sylvester ‘Les Problemès du Peintre’ L’Age Nouveau, 1948, 109.)

Sylvester is referring to the central panel of Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, whose blindfolded figure is sourced from Grünewald’s The Mocking of Christ (1503: Alte Pinakothek, Munich), and to the explicit suffering of the same artist’s aforementioned Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16; Colmar).

|

|

© Tate London 2009 |

It is noteworthy that at this stage, Sylvester — later to be a substantial champion of Bacon’s art — tempers his acknowledgment of Bacon’s power with the remark that, compared to Grünewald, Bacon lacked vision.

Martin Harrison suggests that the orange background palette of Three Studies originates from Bacon’s well-known interest in Degas, illustrated by La Coiffure (c.1896), whilst David Sylvester describes Degas as ‘the marriage of Velázquez and Michelangelo and thus Bacon’s key painter’ (Sylvester 1998, 14). Harrison is more certain of the source of the left-hand panel of Three Studies, which derives from an image in the 1920 book by Baron von Schrenk Notzing entitled Phenomena of Materialisation (Harrison 2005, 40).

|

|

© Tate London 2009 |

Bacon’s habitual destruction of pictures that failed to satisfy his aesthetic standards meant that no new works were shown until he came to an arrangement with Erica Brausen at the Hanover Gallery to put on an exhibition in November 1949. Brausen (d.1992) was instrumental in the publicising of Bacon’s early pictures. Bacon exhibited twelve works in total; eight new pictures in addition to the Three Studies (1944; fig 1.) exhibited as Study I, Study II and Study III , and Figure in a Landscape (1945). The eight new works shown were: Heads I-VI inclusive, Study for Figure (1949; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne -now known as Study from the Human Body) and Study for Portrait (1949; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago — also known as Man in a Blue Box).

That Lewis had not forgotten Bacon was evident in his piece for The Listener on 10 March 1949, when he proclaimed — as he often did — the need for government backing for Britain’s artists. Lewis said that the Tate should be funded for four years at £10,000 per year, and treated as a branch of the health service for the good of the nation. The painters whose work should be chosen, in Lewis’s opinion, were Keith Vaughan, Francis Bacon, Robert Colquhoun, Ceri Richards, John Minton and Merlyn Evans (Lewis 1949a, 408).

A further sign of Lewis’s enthusiasm for Bacon became apparent on 12 May 1949 when he led his Listener piece with news of a Bacon exhibition coming ‘soon’ to the Hanover Gallery (Lewis 1949b, 811). Joe Ackerley had written to Lewis on 10 May: ‘I hope you’ll do the Francis Bacon show for me when it comes’, but a further six months elapsed before an exhibition of eight new works was assembled. At least two pictures — Head I painted in 1948 and Head III discussed below — had already been completed, symptomatic of the difficulties involved in staging a Bacon show at this time. Not only did Bacon destroy works he was unhappy with, it was also not unknown for his canvases to be so recently painted that they were still wet at the exhibition preview. As a taster, Lewis announced in his May article that one of Bacon’s works ‘is already at the gallery’. Lewis then explained delightedly that this was no ordinary picture to be appreciated by ‘the man from the racecourse’ or the ‘cup tie crowd’, the sort of people who liked the picturesque work of Sir Alfred Munnings. Instead, said Lewis, these were works that that type of person would deride; Bacon’s picture was of ‘a man with no top to his head’. It is clear from Lewis’s description (continued below) that the picture is Head III

Bacon’s picture, as usual, is in lamp-black monochrome, the zinc white of the monster’s eyes glittering in the cold crumbling grey of the face. Bacon is a Grand Guignol artist: the mouths in his heads are unpleasant places, evil passions make a glittering white mess of the lips. There are, after all, more things in heaven and earth than shiny horses or juicy satins. There are the fleurs du mal for instance. (Wyndham Lewis The Listener 12 May 1949, 811.)

Lewis’s last two sentences are clearly a dig at Munnings and the Royal Academy style of art he represents, and a reminder that Bacon’s portrayal of the dark side of life is part of a valid tradition exemplified by the poetry of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil.

|

Lewis’s reference to ‘Grand Guignol’, the old-fashioned Parisian theatre of horrors, invites critical parallels with the sinister, macabre and psychological nature of Bacon’s works. However, it also suggests a melodramatic and theatrical element to them that I believe is not present. These early works possess pain, violence and horror more akin to a torture chamber than a histrionic stage production. John Rothenstein picked up on this point when he noted Lawrence Alloway’s similar use of ‘Grand Guignol’ in relation to Bacon. Rothenstein said: ‘it is the reality in the art of Bacon, not the fantasy, that horrifies’ (Alley 15).

Lewis was at last able to review Bacon’s exhibition in November 1949. ‘The Hanover show is of exceptional importance’ he declared. ‘Of the younger painters none actually paints so beautifully as Francis Bacon’ (Lewis 1949c, 860). Bacon, whom Ayrton had described four years earlier as ‘by no means one of the youngest painting generation’ was forty at this time; Lewis himself was sixty-seven that month. Lewis’s praise for the quality of Bacon’s painting skills and his declaration that ‘I have seen painting of his that reminded me of Velázquez ’ suggests an acquaintance with Manvell’s 1946 article quoted earlier. However, it should be noted that in the week of The Listener article (17 November 1949), Bacon himself had referred directly to Velázquez. On 21 November 1949 Time magazine reported Bacon as saying the previous week that ‘one of the problems is to paint like Velázquez but with the texture of a hippopotamus skin’ (‘Survivors’ Time 21 November 1949, 44).

Heads

French philosopher Giles Deleuze is keen to emphasise that Bacon paints heads not faces. Bacon’s project, he says, is to dismantle the face by rubbing or brushing until it loses its form; this enables the rediscovery of the head or makes it emerge from beneath the face (Deleuze 20-21). Deleuze stresses the solitariness and helplessness of the heads: ‘the forces of the cosmos confronting an intergalactic traveller immobile in his capsule’ (58).

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

Head I was painted well before the others, probably in early 1948. It is painted on board as distinct from the ‘wrong’ side of the canvas as the other heads are. Head I possesses both animal and human features which Bacon has conflated into a creature screeching in pain. The focus is on the mouth; Dawn Ades reminds us of Georges Bataille’s assertion in 1930 that ‘human life is concentrated bestially in the mouth’ ( Bataille, ‘La Bouche’, Documents, Paris 1930, 5, 299-300, quoted in Ades, 13). A number of critics have noticed Bacon’s liking for T. S. Eliot, but none has mentioned lines from Ash Wednesday that seem apposite for Head I:

Damp, jaggèd, like an old man’s mouth drivelling, beyond repair,

Or the toothed gullet of an agèd shark

T. S. Eliot Ash Wednesday (1930)

Michael Peppiatt notes affinities between this head and Grünewald’s drawing of a Screaming Head (Berlin-Dahlem) (Peppiatt 1996, 127), though the only actual point of similarity is the near vertical angle of the upturned mouth. Peppiatt suggests later that Bacon’s interest in Grünewald may have resulted from the Picasso drawings from Minotaure (illustrated earlier) (Peppiatt 2008, 102), though Bacon could have observed the Grünewald drawing in Berlin in the late 1920s.

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

Head II has similarities to Head I and possesses the trademark arrows and safety pins that Bacon employed at this time. Anne Baldassari notes Bacon’s remark that he had admired a piece of cloth fastened by a safety pin in the same group of Picasso drawings, published in Minotaure in 1933, that were discussed earlier (Baldassari 150). Bacon later said of this heavily impastoed work: ‘a small picture, and very, very thick. I worked on that for about four months’. It was, said Bacon, one of the few overworked pieces that ‘pulled through’ (Sylvester 1985, 18). This was not a view shared by the Times critic who described it as ‘a mutilated corpse [...] worse than nonsense’ (The Times 22 November 1949, 7).

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

Lewis said of Head III that ‘part of the head is rotting away into space’ (Lewis 1949c, 860). Bataille’s commentary on ‘La Bouche’ is again employed by Ades: ‘the magisterial aspect of the face with its mouth closed, beautiful as a strong-box’ (Bataille, quoted in Ades 15). This face has a personal quality that makes it the most intimate of the six heads, emphasised by the small glasses. A quantity of discoloured white pigment is employed to draw the face to us through a grey film. The dab of zinc white that Lewis observed earlier ensures that the eye at the centre of the picture becomes our focal point.

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

In Head IV, Bacon shows man and beast separately. Lawrence Gowing believed that man and monkey ‘are as solid and spectral as each other. As bestial and as human’ (Gowing quoted in Peppiatt 1996, 128). Again, the use of white on a dark background is a vital component. As Andrew Brighton notes, the figure is teased ‘into three dimensions by painting an ear in highlights and indicating the side of the forehead with a small burst of white’ (Brighton 33). John Rothenstein sees this picture as being ‘like a “dissolve” in a film, when one image moves into another’. (Rothenstein 1962). Such references as this to film, particularly silent film, are often employed in relation to Bacon’s works. For example, Robert Melville, in the last ever issue of Horizon magazine, discusses parallels with ‘the wooden gestures and grimaces of Edna Purviance’(one of Chaplin’s actors), the ‘Odessa steps’ sequence, and the great visual force of Un Chien Andalou (Melville 1951, 420). In that same issue of Horizon the editor Cyril Connolly declared, with Bacon very much in mind:

It is closing-time in the gardens of the West and from now on an artist will be judged only by the resonance of his solitude or the quality of his despair. (Cyril Connolly Horizon Dec. 1949/Jan. 1950, 362.)

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

Head V has become one of the most elusive images produced by Bacon. According to Alley’s 1964 Catalogue Raisonée, it was then owned by a private Swiss collection and last exhibited at Arthur Tooth and Sons in July 1958 (Alley 45). Since then, this image of a head and curtain — adorned with safety pins and bearing similarities to Head II - seems to have disappeared from view and from the orbit of discussion in relation to Bacon’s heads.

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

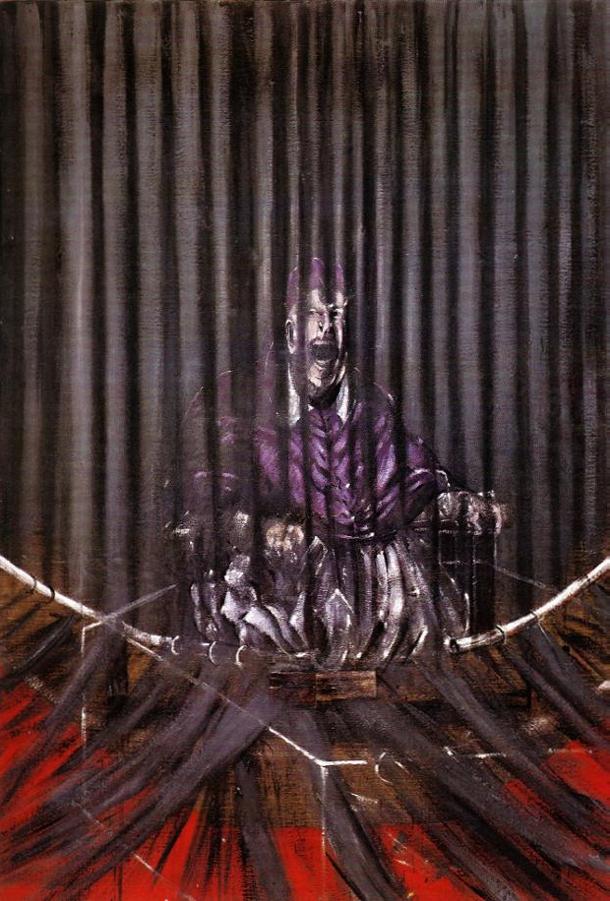

By contrast, Head VI is one of Bacon’s most discussed works; the first surviving piece that he based on Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650). This ‘screaming pope’, like Head III, has a head which dissolves into the roof of the picture. In front of the head is a tassel. Peppiatt suggests that this tassel emphasises the emptiness of the area above the head, and that the subject of the depiction is the scream, as distinct from the head itself (Peppiatt 1996, 129 ). Bacon explained how the use of the delineated box made his works more effective: ‘I cut down the scale of the canvas by drawing in these rectangles which concentrate the image down’ (Sylvester 1985, 22-23).

The open-mouthed screams that characterised a number of Bacon’s works around this time (E.g. Study after Velázquez I and II) have been the subject of numerous theories. Bacon’s observation of Poussin’s Massacre of the Innocents (1630-1) at first hand at the Chateau de Chantilly is well-known, as is his knowledge of the photograph of the gaping nanny from the aforementioned The Battleship Potemkin (see Manvell 1944, between 96 and 97), Picture Post images of Nazi leaders, and his interest in images of oral disease. Bacon himself said that ‘I like [...] the glitter that comes from the mouth [...] I’ve always hoped [...] to paint the mouth like Monet painted a sunset’ (Sylvester 1985, 50). However, the rationale behind his obsession with the tortured cry is more complicated. Dan Farson relates how Bacon was aware of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and tells of the link that John Russell saw between Bacon and Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz (Farson 251):

I saw him open his mouth wide — it gave him a weirdly voracious aspect, as though he wanted to swallow all the air, all the earth, all the men before him. (Joseph Conrad Heart of Darkness (1902))

This suggestion proposes that the subject is trying to draw in air rather than expel it, connecting with the theory that the figure is gasping for breath and therefore relates to Bacon’s own asthmatic attacks (Peppiatt 2006, 24). The box enclosing the figure supports the idea that the scream is silent, unheard, and thus a gesture of futility. Another alternative idea is that the Pope represents the shouting of Bacon’s authoritarian father (35). Martin Harrison suggests the possibility that the scream represents ‘onanistic ecstasy’ (Harrison 208). The expression of pain is an obvious alternative to this, or using knowledge of Bacon’s masochistic tendencies, a conflation of physical pain and sexual pleasure. Deleuze concluded that Bacon had ‘hystericized all the elements of Velázquez ’s painting’ (Deleuze 53).

These same debates can be applied to another of Bacon’s pictures at the 1949 exhibition, Study for Portrait (see below). There are however two important differences compared with Head VI. The man is dressed in a jacket and tie as distinct from papal robes and, unusually for Bacon, there appear to be the shadows of two onlookers in the foreground. The figure is therefore a more formal one and doesn’t possess the isolation that one thinks of in connection with Bacon’s heads and portraits. Later observers noted that in this image, Bacon had prefigured the box-like structure that contained Adolf Eichmann in his trial of 1961.

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

Wyndham Lewis was direct in his praise of a further image from the Hanover Gallery exhibition: ‘In the “Nude” in front of not the least ominous of curtains, about to enter, the artist is seen at his best’ (Lewis 1949c, 860). Lewis refers to Study for Figure, whose title was later changed to Study from the Human Body at Bacon’s request (Alley 46).To emphasise the confusion caused by Bacon’s generic titles, it was illustrated in The Listener as Study for Nude (17 November 1949, 860 — see below).

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

|

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2009 |

This picture, Bacon’s first surviving male nude, was praised by David Sylvester, who declared that ‘its use of grisaille is breathtaking’ (Sylvester 2000, 54). Sylvester also agreed with Lawrence Alloway’s proposition that Bacon had borrowed the diaphanous curtain from Titian’s Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto (1558). Robert Melville proposed that the figure contained hints from Pavel Tchelitchew’s Nude in Space (1926), whilst Martin Harrison illustrates Bonnard’s Nude in front of a Mirror (1931) as representative of the type of image echoed in Study from the Human Body. Bonnard was one of Bacon’s favourite twentieth-century artists and I suggest that Bathing Woman, Seen from the Back (c. 1919: Tate Britain) is the image that possesses parallels of form and technique that most closely ally themselves to Bacon’s picture. There is a similarity of viewpoint and in the way that the upper arm and the elbow extend back towards the viewer. Bonnard was interested in ‘the power of colour to generate light across a surface’ (Watkins 53) and wrote in his diary (in 1927) of the ‘proximity of white making patches of colour luminous’ (69). Bonnard liked also to depict his model through water, a mirror or glass (56) in a manner which parallels Bacon’s use of a translucent curtain. Bacon explained his liking for the Degas device of ‘shuttering’, in which ‘the sensation doesn’t come straight right out at you; it slides slowly and gently through the gaps (Sylvester 2000, 243). Bonnard had also been inspired by Degas’ use of ‘the posed nude as a suitable vehicle for the study of light’ (Watkins 54).

However, Bonnard uses white to provide contrast and emphasis to the golden colour of the body. Bacon utilises it most skilfully to give substance to a thinly-depicted form that is at once behind, in front of, and within the curtain. The body possesses an anaemic pallor, and the head is no more than a semi-solid ovoid, a delineated ear loosely attached to it and the blackness of the void dripping down upon it. The erotic nature of the nude is suggested by the prominence of the buttocks in relation to the upper torso. Bacon reserves his brightest white for the arrows on the shoulders and the safety pin in the curtains.

Bacon’s work is suggestive also of the motion photographs of Eadweard Muybridge that he used as a source for such pictures as Study of a Nude (1952/3). Although no specific image from Muybridge has been suggested as the inspiration for Study from the Human Body, the photograph taken by Muybridge of a female figure (below) was located in Bacon’s studio and provides a good example of possible source material (Harrison 2008, 16).

|

|

© Collection: Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane. |

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

In opposition to the praise from Lewis and Sylvester, Patrick Heron said of Study from the Human Body that ‘nothing could be more summary and flimsy’ and that the curtains were ‘painted with large light brush strokes streaked vertically downwards and barely discharging the dull, slimy mixture upon the canvas’ (Heron 644). Whilst I agree with a further assertion of Heron’s that Bacon probably painted this work quickly, I also contend that it is a marvellous example of the way that Bacon’s minimal application of paint can produce a fully-formed image that provides textural and dimensional complexities for the eye.

In March 1950, Lewis railed against the claim by the New Burlington Galleries to be showing something new: ‘The ballyhoo of newness again, is as old as the hills’ (Lewis 1950a, 522). This theme of the spuriousness of the new is one that Lewis would expand on in his attack on the ‘New Real’ in Demon of Progress in the Arts (1954). ‘There is nothing novel here’ continued Lewis, though that ‘does not mean that Bacon’s pictures are any less fine than when at the Hanover a few months ago’. In fact if there were to be ‘a premium on newness, the “collateral descendant of Francis Bacon” is the only relatively young artist so far qualifying’ (Lewis 1950a, 522). Lewis had compared the artist previously to the Elizabethan Francis Bacon: ‘not like his namesake “the brightest, wisest of mankind”, he is, on the other hand, one of the darkest and most possessed’ (Lewis 1949c, 860). Interestingly, Bacon’s father had traced his ancestry back to Nicholas Bacon, the brother of the childless Elizabethan polymath (Peppiatt 2008, 105), hence Bacon the artist being a collateral descendant of his famous forebear.

As in the previous year, Lewis was ahead of the crowd in his announcement of works by Bacon appearing at the Hanover Gallery, although Eric Newton was actually the first critic into print in respect of the exhibition. On September 17 (not September 7 — Alley p. 284) Newton wrote of ‘pale and suggestively slimy pink forms [that] emerge from a surface of impenetrable primeval grey’ (Sunday Times 17 September 1950, 2). This is clearly a reference to Man at Curtain. Newton added that ‘Mr. Bacon contrives to be both unforgettable and repellent at the same time’. However, Lewis had two months to prepare the piece that appeared in The Listener on 21 September, in which he wrote that:

three large new canvases by Bacon prove him once more to be the most astonishingly sinister artist in England, and one of the most original. (Wyndham Lewis The Listener 21 September 1950, 388.)

In 1949, Lewis had been the only critic to review the early appearance of Head III, so it seems likely that Lewis would have hurried to the Hanover to view Bacon’s work prior to the exhibition beginning on the 14th September. We know from David Sylvester that ‘Bacon delivered the first two images to the gallery, but at the last moment withdrew them from the exhibition, presumably because the third was missing and they had been conceived as a set’ (Sylvester 2000, 44). But we know that three pictures were produced and we know that Lewis saw three new images. The reasons why critics failed to realise that the ‘third’ image (Study II) predated the other two, as distinct from not being produced, is discussed below. This ties in with Michael Peppiatt’s claim that ‘when Bacon delivered his first popes, two of them were delivered still wet to the Hanover just before the show opened’ (Peppiatt 2008, 65) — the third pope was dry because it had been produced some weeks before.

The difficulties of staging a Bacon exhibition were again demonstrated by the absence of a printed catalogue; one was prepared with the heading ‘Francis Bacon: Recent Paintings and The Magdalen’, but Bacon was apparently unable to advise on the number of pictures or their titles prior to the exhibition. In the event, six pictures were hastily assembled, including Figure Study II (1945-6) — whose alternative title, The Magdalen , Bacon later disowned — and the recently-discussed Study from the Human Body (1949), duplicated from the previous exhibition. Thus only four new pictures actually arrived at the Hanover: Man at Curtain (1949-50; Estate of Francis Bacon), described as a sequel to Study from the Human Body and originally believed to have been destroyed, but exhibited at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, in 1998: Study for Figure (1950 — believed destroyed): Fragment of a Crucifixion, (1950; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven): Painting, (1950; Leeds City Art Gallery). Five of the six works, excluding ‘The Magdalene’ lent by the Contemporary Art Society, were for sale at prices ranging from £175 to £350.

But what of Lewis’s ‘three large new canvases’? ‘Perspex’ in Apollo magazine says that Bacon ‘promised three studies from that great artist’s masterly portrait of “Innocent X”, but unfortunately withheld them at the last moment’ (‘Perspex’, Apollo October 1950, 99). Robert Melville attempted to clarify this in World Review three months later:

Two or three months ago I saw at Francis Bacon’s studio a painting that was a kind of paraphrase of the famous portrait of Pope Innocent X by Velázquez [...] Two weeks after I visited his studio, Bacon destroyed this picture [Study after Velázquez],and when the other version [Study after Velázquez II or III] was returned from the framers, it went the same way. The third version never saw the light. (Robert Melville ‘The Iconoclasm of Francis Bacon’ World Review January 1951, 63.)

We now know that Melville was incorrect about the destruction of Study after Velázquez and about the destruction or non-materialisation of Study after Velázquez II. Both pictures were exhibited by the dealers of the Francis Bacon estate, the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York, in 1998; David Sylvester tells how the two pictures were sent away to be reused at an artist’s suppliers in Chelsea, but had been removed from their stretchers and rolled up, and then reappeared nearly half a century later, after Bacon’s death (Sylvester 2000, 44).

Melville was also incorrect about the third version not being produced, as Lewis could doubtless have informed him. ‘Perspex’ noted five works by Bacon as being on display (‘Perspex’ 1950, 99), because the only large work of the four new pictures exhibited, Painting (1950; Leeds City Art Gallery), ‘was delivered late, missing inclusion in both the catalogue and the opening reviews’ (Harrison 2005, 98). This was clearly not one of the three works seen by Lewis, nor is Lewis referring to the three remaining smaller pictures (Man at Curtain, Fragment of a Crucifixion, Study for Figure), which lack any sense of compositional relationship to each other.

|

|

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

Final evidence is provided by the fact that Lewis was unlikely to refer to ‘three large new canvases’, if it were the three smaller pictures (all approx. 55” x 42.75”) that were being displayed alongside the slightly larger Figure Study II (57.25” x 50.75”) and Study from the Human Body (58” x 51.5”). Lewis’s three canvases are almost certainly Study after Velázquez I, II and III, all measuring 78” x 54”, and the epitome of the ‘astonishingly sinister’.

|

|

|

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2009 |

The confusion regarding the non-realisation of the third image arose as follows. Ronald Alley, in his 1964 Catalogue Raisonée, stated that the pictures we know as Study after Velázquez and Study after Velázquez III were the first two ‘variations’, but that ‘he never executed the third and decided at the last moment to withhold the series’ (Alley 1964, 265(D7)). The only references that Alley lists in respect of the two works are the articles by ‘Perspex’ and Melville mentioned above. What is of particular significance is that Alley demonstrates no knowledge of Study after Velázquez II in his catalogue raisonée, and was therefore happy to accept Melville’s assertion that no third image existed.

In 1998 the Francis Bacon estate held an exhibition at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York, where a number of rediscovered Bacons were exhibited for the first time. In the catalogue essay by David Sylvester, he discusses how Bacon completed two ‘with the pope less open mouthed in the second’ (Sylvester 1998, 26), clearly a reference to Studies I and III. Because of the misinformation from Melville and the error of omission from Alley, Sylvester fails to consider that the third image of the series is extant and that that image is Study II. This is despite the fact that Sylvester quotes Alley as saying that the third unrealized image ‘was to have been inextricably entangled with the curtain’ (Sylvester 1998, 26), and that Sylvester himself maintains that this picture was Bacon’s ‘earliest surviving attempt at a three-quarter-length Innocent X’ (Sylvester 2000, 46). Additionally, Study II is an identical size to Studies I and III, has the same crimson and purple colour scheme as Study I (and almost certainly Study III as well), and possesses the same shuttered curtain appearance as both I and III. Crucially, the curtain is clearly disrupted by the man’s leg as indicated by the vertical ribbons losing their parallel aspect. Sylvester himself describes Study II as ‘one of the most iconoclastic images of art history’ (Sylvester 1998, 30) and later suggests that the work should be more correctly known as Untitled (Pope) (Sylvester 2000, 46). Sylvester correctly recognises that the work is a Velázquez variation, but is unable to make the direct connection with Studies I and III because of the information supplied by Melville and Alley. Wyndham Lewis provides the necessary correction to that information when he writes of the ‘three large new canvases’ that he saw at the Hanover Gallery. Finally, it must be mentioned that Sylvester’s 1998 catalogue essay is accompanied by a picture of all three studies (Sylvester 1998, 30) with the caption: ‘right hand painting thought to be destroyed’ — that right hand painting is Study II, which was then on exhibition at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery; it is Study III that is thought to be destroyed, which is why only a black and white image survives.

Bacon and the ‘Blind’ Critic

In May 1951, Lewis announced his resignation as an art critic from The Listener because his deteriorating eyesight meant that he could ‘no longer see a picture’ (Lewis 1951, 765). However, this was not the end of Lewis’s engagement with Bacon’s work. It appears to have been the case that Lewis could still see an outline of a printed image and that pictures could be described to him. This would explain why, in his 1954 book The Demon of Progress in the Arts, he concentrated on artists ‘with whose work I am very familiar because of my “Round the Galleries” in The Listener’ (Lewis 1954, 4). In his introduction to the book, Lewis said:

The English School making its appearance during World War Two, and just after, is actually the finest group of painters and sculptors which England has ever known. I do not refer to achievement; I refer to the existence of so many people who understand painting, and who have revealed a high order of attainment [...] Let me name a few: Ayrton, Bacon, Colquhoun, Craxton, Minton, Passmore (sic.), Richards, Sutherland, Trevelyan. ( Wyndham Lewis Demon of Progress in the Arts 1954, 4.)

Lewis might have added that several of these artists had affinities with the manner in which Lewis had used line and form in his own pictures. For example, Ayrton’s portrait of Sir William Walton (1948; National Portrait Gallery) possesses an angularity of features and of overlapping planes reminiscent of Lewis’s own portraiture. Lewis gave his explanation as to why these artists possessed a quality of which there was ‘unmistakeable evidence’: ‘A combination of [Malraux’s] Musée Sans Murs and of the Golden Arrow, which so quickly wafts one to Paris, has made all these artists as good as Paris-trained’ (Lewis 1954, 4). However, Lewis was worried about a ‘withering disease which might attack the dozen superb image makers’ (5). He illustrates his concern by imagining ‘with horror Francis Bacon’s elephants being stricken with extremism, growing ashen and transparent, their trunks drooping, and falling in a heap of white ashes at the foot of their canvas, livid and vast and blank’ (6) — a reference to Bacon’s Elephant Fording a River (1952; Private Collection).

Lewis’s illustrates his disquiet by an examination of six works of art. The first two, by Bombelli and Engel-Pak are, according to Lewis, ‘designed to illustrate the terrible pictorial aberration whose idiot name Real cannot be tolerated outside of the pathological clinic’ (Lewis 1954, 50-51). By contrast, Lewis praises four other pictures by Minton, Ayrton, Colquhoun and Bacon. He says of Bacon’s Man in a Chair (1953; Hess Art Collection, Berne — now known as Study for a Portrait) that ‘to the uninitiated [it] doesn’t belong to the traditional order’ and continues ‘the Caprichos of Goya and pictures by the Flemish artist Hieronymus Bosch, are very like the grotesqueries of Francis Bacon. Also the ethical and literary impulses throughout the work of Bacon constitute him an artist at the opposite pole to the pretentious blanks of Réalités Nouvelles’ (50-51). Lewis explains that ‘these four pictures are all of them styled “progressive” and “modernistic”; but...there would be no sense in their “advancing” into the nothingness and nullity of the “New Real”’ (50-51). Lewis clearly sees this new movement of ‘diagrammists of zero’ as an attack on painters in the European tradition, such as Bacon; John Rothenstein said of Bacon that ‘his ambition is to take shocking or unheard-of material and deliver it in the European grand manner’ (Rothenstein 1974, 165).

Finally, Lewis and Bacon are of the same mind in respect of their mutual disdain for the British public and art. Lewis says that ‘the great majority of the 40 million people in Britain are culturally no later than the Palaeolithic’ (Lewis 1954, 57), whilst Bacon concludes that ‘ninety-five per cent of people , are absolute fools, and they’re bigger fools about painting than anything else [...] very, very few people are aesthetically touched by painting’ (Sylvester 2000, 249).

Conclusion

Wyndham Lewis was at the forefront of the promulgation of Bacon’s work. He wrote to a well-informed readership of about 150,000 in The Listener, and consistently used Bacon as an example of all that deserved support in the field of contemporary art. Lewis’s observations drew the public’s attention to important exhibitions of Bacon’s works and provided a colourful and descriptive interpretation of its merits. Additionally, they also provide useful clues to the early exhibition of Head III and the three Studies after Velázquez.

A number of themes have become apparent during this examination of Bacon’s early artistic career. For example, little emphasis has been placed on how few in number of new works actually made it to gallery exhibitions. The Hanover Gallery had to supplement these pictures with ones that had been previously exhibited. Works arrived at the gallery still wet because they were so recently painted, or didn’t materialise until after the exhibition was underway. In the 1950 Hanover exhibition only three new works were displayed until Painting (1950; Leeds City Art Gallery) arrived to complete the quartet; the three Studies after Velázquez were withdrawn by Bacon as the exhibition was about to begin. This scarcity of new exhibits however did not prove detrimental to Bacon, but instead enabled critics to concentrate on the few large canvases that were being shown.

A final thought is that critics have made assumptions based on Bacon’s own pronouncements, whilst they acknowledged also that Bacon was careful to cultivate an air of mystery about his sources and inspirations. Bacon’s own words need to be considered in conjunction with those of contemporary and modern critics, and with factual evidence provided by source documentation, in order to obtain a greater understanding of his oeuvre.

Bibliography

Ackerley, J. R. 1949. Letter from J. R. Ackerley to Wyndham Lewis 10 May 1949. Wyndham Lewis Collection in Cornell University Library, Box 85, Folder 23. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University.

Ades, Dawn and Andrew Forge. 1985. Francis Bacon. London: Tate Gallery in association with Thames & Hudson.

Alley, Ronald. 1964. Francis Bacon. London: Thames and Hudson.

Ayrton, Michael. 1945. ‘Art’. The Spectator. April 13, 335.

Baldassari, Anne. 2005. Bacon Picasso: The Life of Images. Exh. cat. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

Brighton, Andrew.2001. Francis Bacon. London: Tate Publishing.

Deleuze Gilles.2003 [1981] Francis Bacon: the Logic of Sensation. London: Continuum.

Farr, Dennis. 1999. Francis Bacon: A Retrospective. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale Centre for British Art.

Farson, Daniel. 1993. The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon. London: Century Random House.

Gale, Matthew and Chris Stephens. 2008. Francis Bacon. London: Tate Publishing.

Hammer, Martin. 2005. Bacon and Sutherland. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

_______. 2005. ‘Clearing Away the Screens’ in exh. cat. Francis Bacon: Portraits and Heads. Edinburgh: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

Hanover Gallery. 1949. Francis Bacon Paintings — Robin Ironside Coloured Drawings. Exh. cat. London.

_____. 1950. Francis Bacon Recent Paintings — Hilly Paintings. Exh. cat. London.

Harrison, Martin. 2005. In Camera Francis Bacon. London: Thames & Hudson.

_______. 2008. Francis Bacon Incunabula. London: Thames & Hudson.

Heron, Patrick. 1949. ‘Francis Bacon’. The New Statesman and Nation. 3 December, 643-644.

Hyman, James. 2001. The Battle for Realism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Lewis, Wyndham. 1946. ‘Towards an Earth Culture: The Eclectic Culture of the Transition’ in Walter Michel and C. J. Fox Wyndham Lewis on Art: Collected Writings 1913-1956. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.

_______. 1949a. ‘Round the London Galleries’. The Listener, 10 March, 408.

_______. 1949b. ‘Round the London Art Galleries’. The Listener, 12 May, 811-812.

_______. 1949c. ‘Round the London Art Galleries’. The Listener, 17 November, 860.

_______. 1950a. ‘Round the London Galleries’. The Listener, 23 March, 522.

_______. 1950b. ‘Round the London Art Galleries’. The Listener, 21 September, 388.

_______. 1951. ‘The Sea-Mists of the Winter’. The Listener, 10 May, 765.

_______. 1954. The Demon of Progress in the Arts. London: Methuen.

Manvell, Roger. 1944. Film. [Harmondsworth]: Penguin.

_______. (as Roger Marvell). 1946. ‘New Pictures’. New Statesman and Nation. 16 February, 119.

Melville, Robert. 1949. ‘Francis Bacon’. Horizon, December 1949-January 1950, 419-423.

_______. 1951. ‘The Iconoclasm of Francis Bacon’. World Review, January, 63-67.

Mortimer, Raymond. 1945. ‘At the Lefevre’. New Statesman and Nation, April 14, 239.

Newton, Eric. 1950. ‘An Unhappy Genius’. The Sunday Times, 17 September, 2.

Peppiatt, Michael. 1996. Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

_______. 2006. Francis Bacon in the 1950s. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

_______. 2008. Francis Bacon: Studies for a Portrait. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

‘Perspex’. 1950. ‘Current Shows and Comments’. Apollo, October, 99.

Rose, W. K. 1963. The Letters of Wyndham Lewis. London: Methuen.

Rothenstein, John (intro.). 1962. Francis Bacon. Exh. cat. London: Tate Gallery.

_______. 1974. Modern English Painters — Wood to Hockney. London: MacDonald and Jane’s.

Russell, John. 1964. Francis Bacon. London: Methuen.

Shafrazi, Tony (intro.). 1998. Francis Bacon: Important Paintings from the Estate. New York: Tony Shafrazi Gallery.

Sylvester, David. 1948 ‘Les Problèmes du Peintre: Paris-Londres 1947’. L’Age Nouveau, 31, 107-110.

_______. 1985 [1975]. Interviews with Francis Bacon 1962-1979. London: Thames and Hudson.

_______. 1998. Francis Bacon: Images of the Human Body. Exh. cat. London: The Hayward Gallery.

_______. 2000. Looking Back at Francis Bacon. London: Thames and Hudson.

Time. 1949. ‘Survivors’. 21 November, 44.

The Times. 1949. ‘Art Exhibitions: Mr. Francis Bacon’. 22 November, 7.

The Times. 1950. ‘Hanover Gallery: Mr. Francis Bacon’s Paintings’. 22 September, 6.

Watkins, Nicholas. 1998. Bonnard: Colour and Light. London: Tate Gallery.